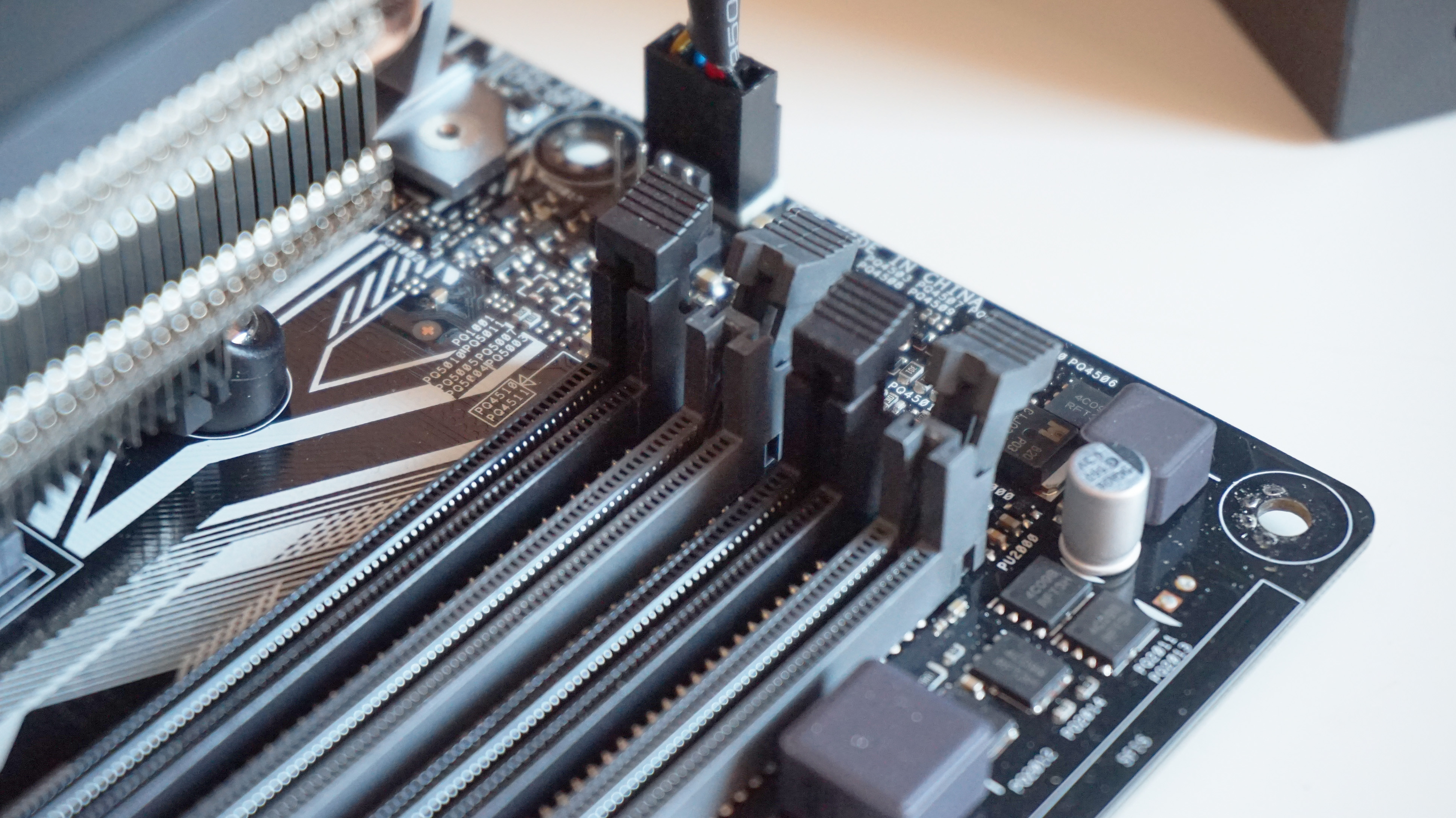

If you have 2 sticks of RAM, you'll start from the slot closest to the 24-pin and put one in that slot, skip a slot, and then the second RAM stick will go in the third slot. If you only have 1 stick of RAM then it will go in the third slot from the 24-pin. With 16 GB SO-DIMM RAM modules, it is possible to double the RAM in notebooks, miniature servers, and small form factor PCs, but many processors are not compatible with the tech.

If you’ve ever taken a look at a product page for sticks of RAM, or at the specifications for a CPU or motherboard, you’ve probably seen “memory channels” mentioned.

For many beginners, this sparks questions like, “What’s the deal? Does dual-channel mean I can only use two sticks? What do multiple channels do that one channel doesn’t? Can I use quad-channel RAM on a dual-channel motherboard?”

The answers to those questions and more can be found below, so read on!

RAM Channels: The What

What Slots Should Ram Go In The City

The manual suggests that it should have 4 slots. If it does have 4 slots then your options increase. For example you could add another 2 x 512 MB RAM in dual channel mode in the remaining two empty slots. This would give you a total of 2 GB (4 x 512 MB) Personally in that event I would go for 2 x 1GB RAM in dual channel mode in the 2 empty slots. Most consumer grade memory features a single rank, though higher capacity modules are usually dual rank, while server grade memory is often quad-rank. Identifying if your memory is dual or single.

Simply put, memory channels are the links between your RAM and your CPU through which data moves between the two. The RAM is the computer’s short-term memory, and the CPU is the main processor that does stuff with the information in the memory; the RAM channels are how that information moves back and forth.

To be clear, these memory channels are actual wires that exist on/in the motherboard. Though RAM kits may call their arrangements “channels,” the actual number of channels and the number of RAM sticks are independent of each other; any mention of channel count on a RAM kit’s product/specification page is just an informal, technically-incorrect way of referring to how many sticks of RAM there are in the kit. In addition, the number of RAM slots on a motherboard is independent of the number of memory channels. A channel needs only one stick to be used, and any more than that doesn’t necessarily stop things from working.

Most modern motherboards have two to four memory channels. On the AMD side, every AM4 socket motherboard has two memory channels, and every TR4 socket motherboard has four channels. On Intel’s side, every LGA 1151 motherboard has two memory channels, and every LGA 2066 motherboard has four memory channels. This means that, on our main chart, every configuration up to and including the “Enthusiast” tier has two memory channels. The “Extremist” and “Monstrous” tiers are the only rows which have four memory channels.

In addition, CPUs also support a certain maximum amount of memory channels. You don’t really need to worry about this, as every CPU will handle the amount of memory channels available on their supporting motherboards. There are only two notable exceptions: Intel’s i5-7640X and i7-7740X, which are both LGA 2066 CPUs, and very odd purchases anyway.

RAM Channels: The How

To explain what multiple channels do, let’s try an analogy.

Imagine a manufacturer of products:

Let’s say this manufacturer (your CPU), with potentially many factories (cores) in need of materials, makes orders for materials from only one supplier (memory channel). Even if the supplier has a whole lot of materials (capacity / stored data), and may run multiple warehouses (RAM sticks) of their own, it has a limited capacity for making shipments, and so can’t handle multiple shipments to the manufacturer at once. There may be multiple shipments ready to go, but they can’t actually start shipping until the current shipment is done.

A single-channel supplier warehouse attempting to serve a quad-factory manufacturer with one truck

The problem is, this manufacturer can often use materials faster than their supplier can ship them, and the delay from waiting on the supplier’s logistics system for consecutive orders can slow things down. Especially when this manufacturer’s factories are being heavily loaded with orders of their own from vendors and customers (your other components) while relying on materials orders, the supplier can pose a problem.

So, the manufacturer contracts with a second supplier in addition to the first. Now, the manufacturer does something efficient: They alternate orders between the two suppliers. This way, the manufacturer can have two simultaneous shipments coming their way, and they suddenly find that waiting on consecutive orders to be shipped is now significantly less of an issue, since their effective capacity for getting shipments has been doubled. This same idea can extend even further across more suppliers.

Really, how much the number of suppliers the manufacturer uses actually matters all depends on: how quickly materials are being used, how many factories they have (since each might come in need of materials at any given moment), how busy the manufacturer or specific factories are, and how quickly the suppliers themselves can send shipments to the manufacturer. Most of the time, this isn’t a big deal, but when things line up well or poorly, the number of suppliers (i.e. memory channels) can make a notable difference.

DDR5: Breaking the Status Quo?

If you’ve been keeping up-to-date on DDR5 memory, you may have seen mention of DDR5 RAM sticks (yes, each stick itself) having two memory channels. And what they’re saying is true, from a certain point-of-view. From my understanding, these “channels” aren’t like the memory channels described above, but still apply a similar (though not quite the same) concept on the stick-by-stick level.

Micron, one of the only three manufacturers of memory chips, describes this development as “essentially turning an 8-channel system as we know it today into a 16-channel system.” So what is going on here?

From what I can tell, it seems that each stick can work with two separate bunches of data, though it can’t be moving data from both bunches across the actual (physical, on-the-motherboard) channels at the same time. For example, a stick could be receiving data on one half, and be preparing to send data on the other half in the meantime. This is still a significant improvement in design over previous iterations of RAM like DDR4, though not quite as dramatic as it sounds at first. Reality is often disappointing; we’ll just have to wait and see if this turns out to actually be the case.

Conclusion

Let’s make one thing clear: to use multiple channels, you need multiple RAM sticks. Those RAM sticks should be installed so that you have at least one stick in each channel. The best thing you can do here is place your RAM sticks according to what your motherboard manual says. Though the slots are usually color-coded, this isn’t always the case, so check that motherboard manual.

For many country versions of our main chart, the linked 8GB options (and every 4GB option) are single sticks; so, without another stick of RAM, only one memory channel will be used. This is not the case everywhere, though, and all 8GB kits in the US version of the chart have two sticks for dual-channel. The 16GB options are dominated by two-stick 16GB kits, though some countries still have one-stick options linked. However, it’s up to you to choose how many sticks will work best for your system and your program tasks—there’s no need to get the exact kits we link.

Adding additional RAM memory to computer had been always one of the easiest and efficient upgrades. Over years with baggage of hardware generations and new technologies it can get tricky.

What Slots Should Ram Go In The World

When installing memory it’s not important what to do, but more important to do it right

Choose memory

There are two main factors in memory: type and speed.

By type most of it is one of DDR, DDR2 or DDR3 (unless you are looking at really old computer). Memory of different types is not compatible mechanically or electronically. Motherboards usually have slots for one specific kind of memory, some rare models can support memory of two types (but not at the same time).

Speed of memory is faster for newer types, but also differs in margins of every type. Motherboards might only support slower speed than memory can come with. Memory of different speeds will in general work with any motherboard of required type. Slow memory will work at its speed even if motherboard can go faster. Fast memory will slow down to match motherboard if needed.

So you need memory that matches motherboard in type and (best case) speed. If adding memory it is also good idea that new modules match old ones in parameters and brand.

Manufacturers always provide (in manual and online) information on what memory motherboard supports and larger brands even offer lists of practically tested modules for each motherboard.

Choose slots

I remember times when you just had to stick modules in, but those are gone.

Currently most of motherboards/processor combos support at least two memory channels. I think there are already rare (for now) configurations with three channels.

Different channels correspond to different physical slots on board. The idea is that memory must be balanced between channels and that requires them to be filled in specific order.

Motherboard manual has diagram of slot channels and numbers. For example like this one:

Letter commonly refer to channel, numbers commonly refer to order inside channel. In usual case (when manual doesn’t have other explicit instructions) slots must be filled in following order:

- First slot of first channel (A1 in example)

- First slot of second channel (B1)

- Second slot of first channel (A2)

- Second slot of second channel (B2)

- And so on.

If you need to install multiply modules it is best to add them one by one.

What Slots Should My Ram Go In

Overall

Installing memory is not hard, but my advice is to have motherboard manual open and ready. Those slots rarely come in any kind of sane order. I had recently upgraded computer for a friend and it took me five attempts to get kit of 3x2GB memory modules working correctly.